Preface

Buildings talk. Walls, floors, ceilings, roofs, footings, slabs, windows, doors, linings, joinery - all talk. They talk about the things they do, of what they’re made, and from where they came. This studio begins by critically questioning the materials we use and surround ourselves with. It advocates for our contemporary material culture to be repositioned, away from an emphasis on the new and the high-tech, from global supply chains of standardised proprietary items made from carbon intensive, extracted materials. Instead, we look to the old for a new material ecology. To learn from the ways we’ve built for millennia, to materials which rarely travelled far from their source, or from where they were grown. To buildings which are regionally sourced, and permitted to be altered, reused or decompose, returning to the ground without doing harm. Importantly, these are buildings which retain a direct link to their surrounding country. This is an old material culture to be renewed, broadening our capacity to design our built environment to be more sustainable, resilient, and adaptable.

This project renews two ‘old’ materials - hemp and cork - and reintroduces them to Sydney’s construction vocabulary. Additionally, to inform a design concerned with housing the needs of twenty-one older women we look to the ‘old’ typology of the hofje, where life is focussed on medium-density communal courtyard living. These old materials and typologies become a point of departure in our investigation on how these can be best reappropriated for a new way of contemporary building and living in Sydney.

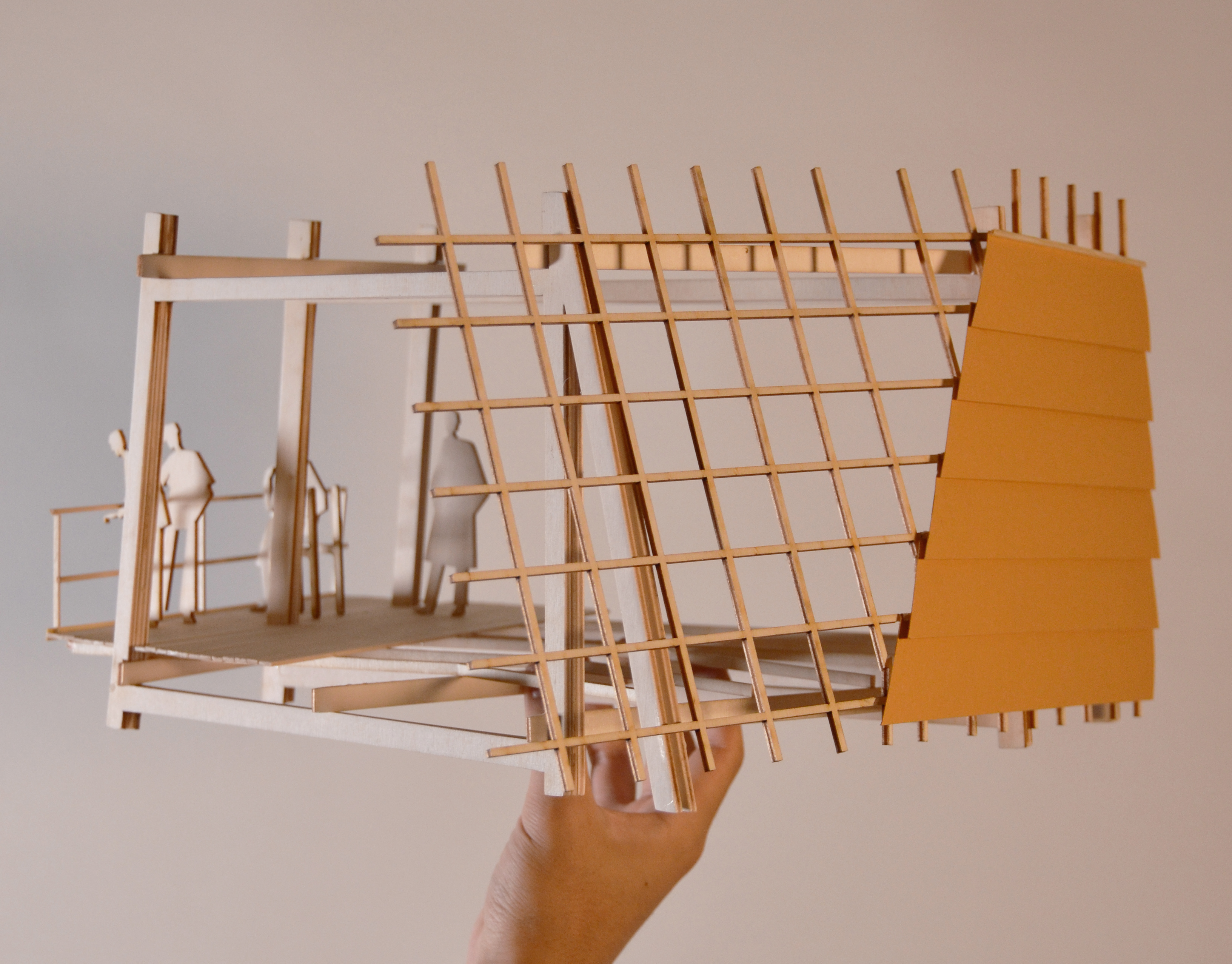

Render Image - Installation of prefrabricated hemp panels

Position

Statement

Our contemporary material culture is suffocating. Defined by elaborate global supply chains, enormous economies of scale and limited to restrictive proprietary products, this is a culture where architects are increasingly relegated to specifiers of high-tech products with untraceable origins. Our alarming lack of agency and authorship in this culture not only limits our creative potential, but also limits the ability of our critical skills to radically reposition this cultural attitude. What is urgently necessary is a culture which looks beyond the confines of the site boundary, to its wider context, its networks, and connectedness to country. Facing immanent ecological breakdown, architects must now consider the present and future impacts of every choice made in the design and construction process. To not just do less harm, but net good, we need to “become the stewards of the environment rather than its destroyers”.

Layers of oil-based materials make up a contemporary wall. Preoccupied with thermal performance, these walls have little regard to their embodied carbon. If it is to be labelled “sustainable” a detail may show more than ten highly specific materials and membranes arranged to form a thin non-breathable barrier. Post-carbon researcher Paloma Gormley underscores the delusion that the buildings using these maintenance free materials are meant to last forever. In reality they are often replaced wholesale, because our culture has made it terrifyingly cheap and efficient to do in the first place. Our position echoes this call for a different culture and a different approach of longevity in design. Cork and hemp are both ancient, non-extractive, bio-degradable and regenerative fibre materials which hold incredible potential for redefining the future of sustainability in the built environment. Architecture is effectively grown using these ‘hairy’ materials, creating both a tangible and temporal link between the building and the country from which it was cultivated.

This direct link demands a careful consideration for land which lies beyond the construction site, an urgent responsibility, one that resonates with the long overdue call to recognise the culture of Australia’s first nations peoples and their relationship and respect to country. Locally grown, low-tech materials with an awareness of the circular economy, their production, use, and decomposition over time creates a material culture which understands country as a living entity, which looks to the built environment not in isolation, but as part of an interconnected system of humans, nature, and culture.

Our design proposal has responded to these calls for a renewed material culture. Hemp and cork construction processes create an opportunity for a low-tech, carbon negative building. The nature of these materials encourages their use in prefabricated systems, ones which are editable and flexible, in form and function, which aims to increase both the agency of the multiple end users and the longevity of the building as a whole. The history of the project’s site, as a culturally significant network of wetlands and creeks pre-colonisation to the heavily polluted industrial canal which we see today is an important consideration. Hemp’s ability to decontaminate soils encourages it to be locally grown on empty industrial brownfield sites along the canal, hoping to aid in the inevitable future regeneration of a once thriving biodiverse area.

Reacting against our contemporary global material culture, our proposal expresses a concern for the local. Future transformation of a climate conscious construction industry will demand this, as must architects who consider their impact on country.

Render Image - View of the design project’s communal courtyard

Project

Overview & Reflection

To embark on this studio meant to follow my curiosity and begin to deeply question the materials we use in architectural design. As young designers at this institution we’re often inducted into our practice by a rudimentary questioning of the very things we use to create, particularly our materials, their properties, their opportunities, and their origins. Yet, I’ve found that this emphasis quickly falls to the wayside as studios - and their briefs and tutors - become preoccupied with a spectrum of other concerns, some valuable, others questionable. Ranging from human centred design functions or social, spatial, and environmental performance (still important) or far worse they descend to patronising and intangible polemical debates on arbitrary style and taste. While some of these preoccupations are incredibly necessary others bog a student down in the haughty status quo. Frankly, quibbling over superficial and personal theoretical opinions while the world enters climate catastrophe is something I hope to avoid in the master’s degree. I gladly found the opportunity to be challeneged and rekindle my interest in radically broadening my material vocabulary, as well as taking responsibility for our environment and considering indigenous country in this design project.

The studio began with a comprehensive investigation of hemp and cork, two ‘old’ materials which have made a recent, and global, resurgence in architectural design. The origins, cultivation, and intrinsic properties of these humble materials challenge the designer to tease out opportunities, work with - and respect - their strengths, creating in the process a design which is incredibly beautiful, radical and responsible. Precedents which demonstrate this new logic were explored and they do indeed question the status quo of our material culture, evaluating what and how we extract from the planet the stuff we use to build. These are lessons which redefine what must be considered valuable and scarce in the design process, what must be permanent (if anything) and what can be removed or changed. This investigation demonstrates that the current material vocabulary of extracted and carbon emitting materials such as steel, concrete and aluminium, must be used sparingly, if at all. Grown from the soil, carbon sequestering materials can return to their ecosystems, or be regrown or used again and again. This is a studio which points to the possibilities of a circular design process and economy which considers the past, present, and future of the built environment.

Connecting practice to country is a long overdue responsibility for all designers, no matter what logics one follows. However, growing, and extracting materials for the built environment immediately links the design process and resulting architecture to the country from which it came. From these responsibilities come profound opportunities which weave local and distant first nations culture and history into the buildings very fabric and broaden the respect needed for the design process beyond the confines of the site boundary. Materials that are grown locally, or extracted far away must always respect the wishes and customs of traditional landowners, they have the opportunity to be grown responsibly and do net good, not harm.

These lessons were all layered into our final design project to create a courtyard typology aimed at housing twenty-one older women. This is a diverse client group with a range of different livelihoods and ambitions.The planning accounts for wider occupancy needs; grandchildren, partners, family, friends, carers, or accessibility requirements. It accommodates the most important to the most routine of life’s moments; Christmas lunches, birthdays, gardening, wakes, yoga, mah Jong and bridge clubs, workshops and reading. We’ve aimed to work with hemp’s ability to be regrown in less than 4 months to create a floorplan which can be continuously altered to suit the changing needs of the occupants. This is a design which recognises the required longevity and adaptability of each building component and intelligently employs specific materials to serve each purpose. This is informed by Stewart Brand’s Six ‘S’s’ (Site, Structure, Services, Skin, Space Plan, Stuff), which orders building components based on their permanence.

Learning with our hands by modelling, making and testing materials brought us into contact with the tactility of specific material properties and processes. This studio has encouraged me to interrogate how material and industrial cultures shape the world. It has stressed the importance of a continuous exploration of materials which challenge regulations, supply chains and processes in order to produce proposals that offer a radical yet viable alternative to the status quo.

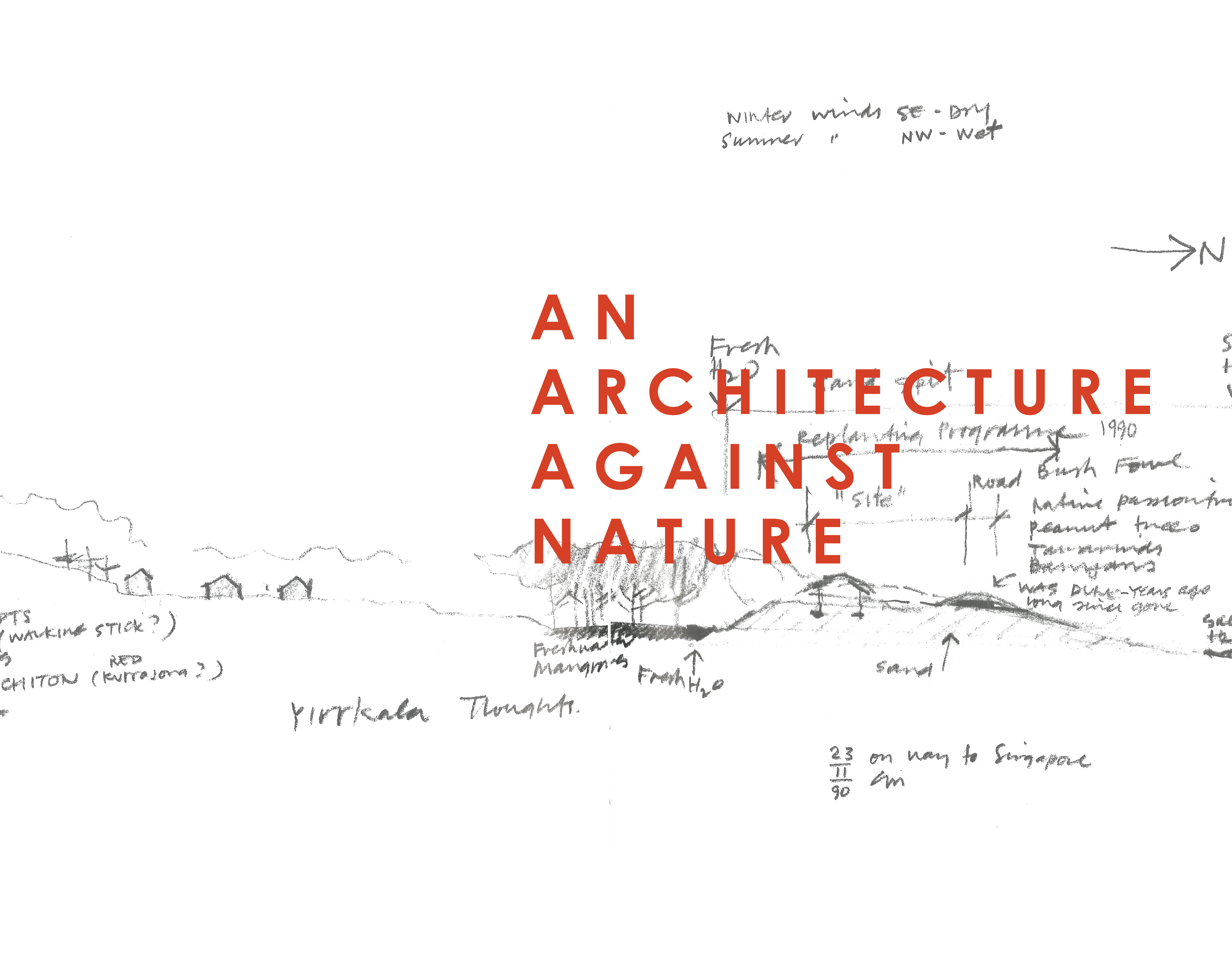

Site Aerial Sketch - Shea’s Creek & industrial Alexandria highlighted in the background

Connecting

with Country

“We need to think beyond site boundaries and consider the concept of cultural landscapes.”

— Elle Davidson, Balanggarra Woman

— Elle Davidson, Balanggarra Woman

“Country-focused design is both process and product that goes beyond stylised homage to plants and animals. Every step from the first marks on a page to governments’ decisions, materials used in building fabric has respect for Country.”

— Alison Page, Walbanga and Wadi Wadi Woman

— Alison Page, Walbanga and Wadi Wadi Woman

Elle Davidson and Alison Page both stress the need to reframe Country to be at the centre of design decisions. This is a logic which presents an important opportunity in our collective endeavour to build a more sustainable future. A logic which learns from an Aboriginal world view, one where humans, plants, animals and natural systems are considered as equally important and interconnected actors guiding our interventions as architects. Designing buildings which are effectively grown in our local and distant landscapes creates an immediate tangible link between the architecture and Country from which it is cultivated. This innate link forms the heart of our design project and calls for a respect for Country and its history - past, present and future - beyond the confines of our site boundaries at Mitchell Road, Alexandria.

The sites history from pre-colonisation to present day is one which has unfolded many times before in Australia’s urban centres. This is a history of dispossession, exploitation, and destruction. Alexandria lies on Gadigal Country, at the confluence of creeks channelling rainwater from the sandy hills and ridges of land now known as Erskineville, Newtown, Redfern and Surry Hills. These waterways met to form Sheas Creek, winding past Mitchell Road and Sydney Park to form wetlands and a rich tidal salt marsh by the time it had reached Botany Bay. The area was an important food resource for local first nations people, yet they were quickly expelled as the new colony expanded south. Legislation banning polluting industries from the city centre dramatically altered the creek as brickmakers, tanneries, wool washes, slaughterhouses, and chemical manufactures were pushed to the area, finding the waterways an expedient solution to drain noxious effluent to Botany Bay. The creek was later dredged, and it banks destroyed and widened to make the shallow Alexandria canal to service the heavy industry along its course. All in vain, the canal was never used as intended, yet remains to this day one of the most polluted water courses in the southern hemisphere.3 Acknowledging the site’s history of colonial infrastructure causing violent destruction and dispossession demands a design response which deeply reflects on its local impacts and past wrongdoings. If connecting with Country encourages architecture to be constructed from locally sourced, sustainable building materials, there exists an opportunity to grow these materials along the deindustrialising banks of the canal, binding these materials with Country.

Following the rehabilitation of nearby Syndney Park from polluted brickpit to parkland, as Alexandria continues its trend of deindustrialisation, the inner-city area will transform and consider how it can return these brownfield sites to their once thriving ecosystem. The design proposes growing the hemp needed for construction in the many vacant plots that line the canal. Hemp can draw out and filter toxins in the soil and water, removing decades of waste. After it has been used it can be returned to the ground and Country to decompose as fertiliser. This process forms the foundation of a circular local economy, stressing that impact of materiality on Country must be considered at all stages of the building’s life cycle. We acknowledge that hemp is not an indigenous plant, and that this opportunity must be responsibly managed alongside consenting traditional landowners to prevent further damage to Country from invasive species and weeds. It is hoped that once the land becomes clean enough, the native landscape can be reinstated, encouraged, and cared for. The resulting design proposal will have local stories and cultural values literally built into its walls. Such an expression in a locally grown, low-tech building will help to underscore our relationship to nature and reinforce an awareness of the local country as a living entity, compelling a new culture of care and collective identity.

Connecting

With Country

Sheas Creek Site Analysis

These collages and maps present a closer look at the radical yet viable strategy of locally growing hemp required for the construction of the proposal. The collages represent a decaying industrial landscape built on the banks of the Alexandria Canal. Hemp can be part of the process to rehabilitate the polluted land on which these factories and warehouses sit. The Alexandria Canal can be returned to the vibrant waterway it was, following the many post-industrial waterway revitalisations around Sydney, including Sydney Park, Johnsons Creek in Annandale and Powells Creek in Olympic Park. These precedents have shown that design and architecture can be central to the solution of reconciliation and caring for Country.

Four brownfield sites have been identified as vacant land currently viable to grow hemp. This is land which backs onto the canal and lies unused and polluted. Combined, the 10 acres of these four sites can grow enough hemp to build 8 standard family homes in a year. It is estimated that our proposal will need at least 20 acres of land, farmed over the course of a year. As hemp takes only 3-4 months to grow, sites sitting in limbo between demolition and construction could also be used.

Sheas Creek will one day be rehabilitated as industry declines and the city expands. Hemp can be part of this restoration, redefining a local material culture.

Hempcrete

Material Process & Testing

1 : 1 Model Making

The aim is to obtain an aerated mix resembling sticky crumble in which the hemp particles are well covered by the lime binder without the building material being too wet.

01 The hemp should be as clean and dry as possible with minimal dust or foreign matter. First, pour water into the pan mixer and allow it to coat the walls, then add the hemp. Allow the ingredients to mix for a few minutes till all of the hemp has been coated with water. It is important that all surfaces are wetted so that the binder can adhere to the hemp, but it must not become soggy.

02 Measure out the quantity of lime binder. You should aim to have a mix to the ratio of 1kg hemp to 1.8kg lime binder to 3 litres of water.

03 Add the binder gradually to the mixer and mix for 5 – 10 mins. This is dusty initially. Wear a dust mask. It’s important that all of the hemp is coated in binder.

04 It’s important not to make the mixture too wet as you need the binder to coat the hemp. Vary the water to suit the conditions by water spraying the mix slightly in very hot weather. If the mixture is too wet and tamped firmly, a paste is forced to the outside of the mix and the lime solution leaches out of the formwork resulting in a poor mix.

05 Once it is mixed the hempcrete can be placed into prefabricated formwork. All timber must be coated thoroughly with linseed oil to prevent it drawing moisture from the mix and warping.

06 Once placed, the hempcrete is tamped lightly into place, with minimal compression (unlike rammed earth). Through pozzolanic chemical reactions between the components of calcium carbonate in the lime and the silica in the hemp, the mixture petrifies and becomes a light, yet quite resistant solid.

07 The hemp mix takes about 7 days to dry, and the curing process takes about 3 months. While the hemp is being mixed and is curing it must be protected from moisture exposure. Allowances for conduits and pipes must be installed before the mix is added. Any breathable renders can be applied after the mix has been cured.

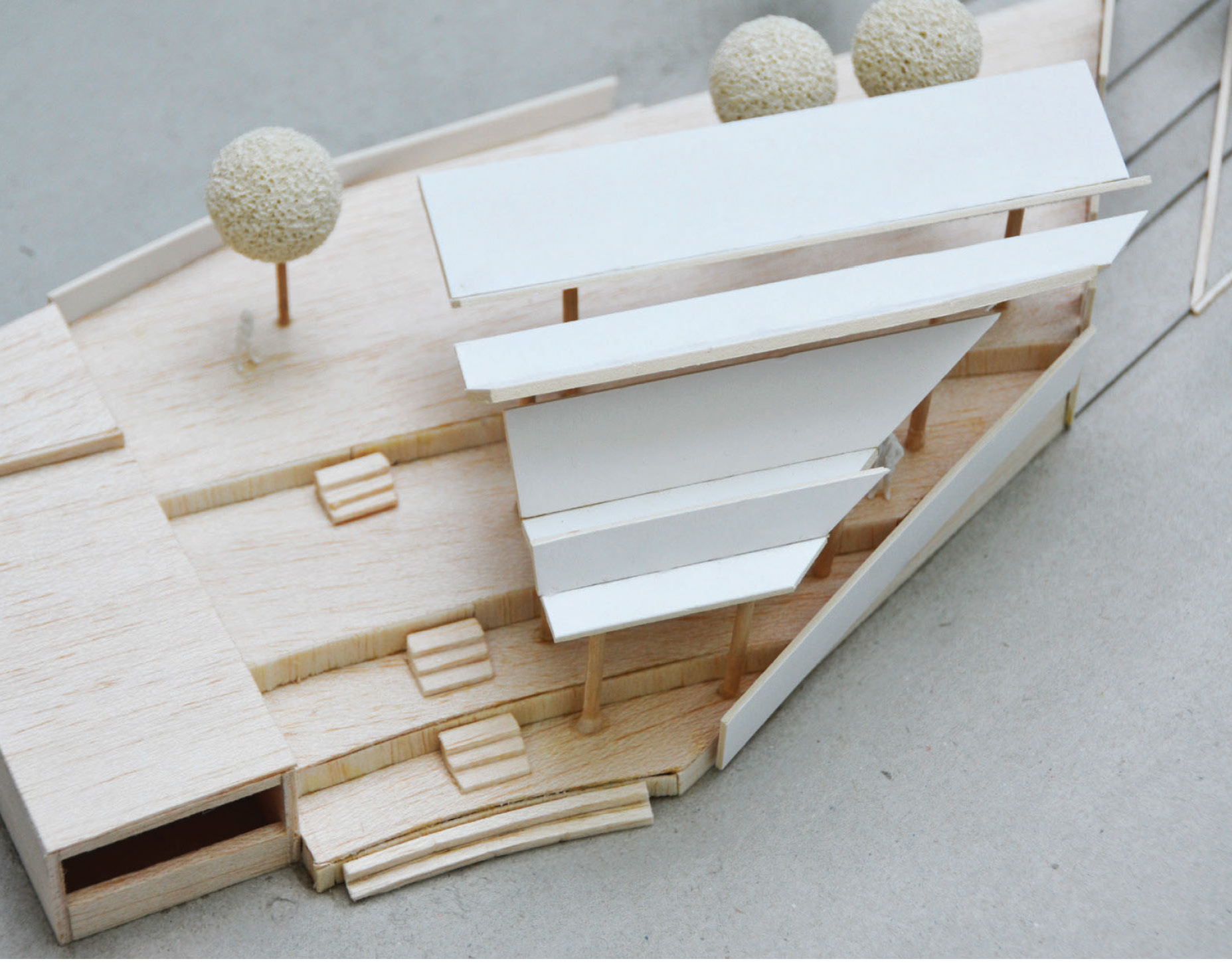

1 : 200 Model Photograph

Design

Project

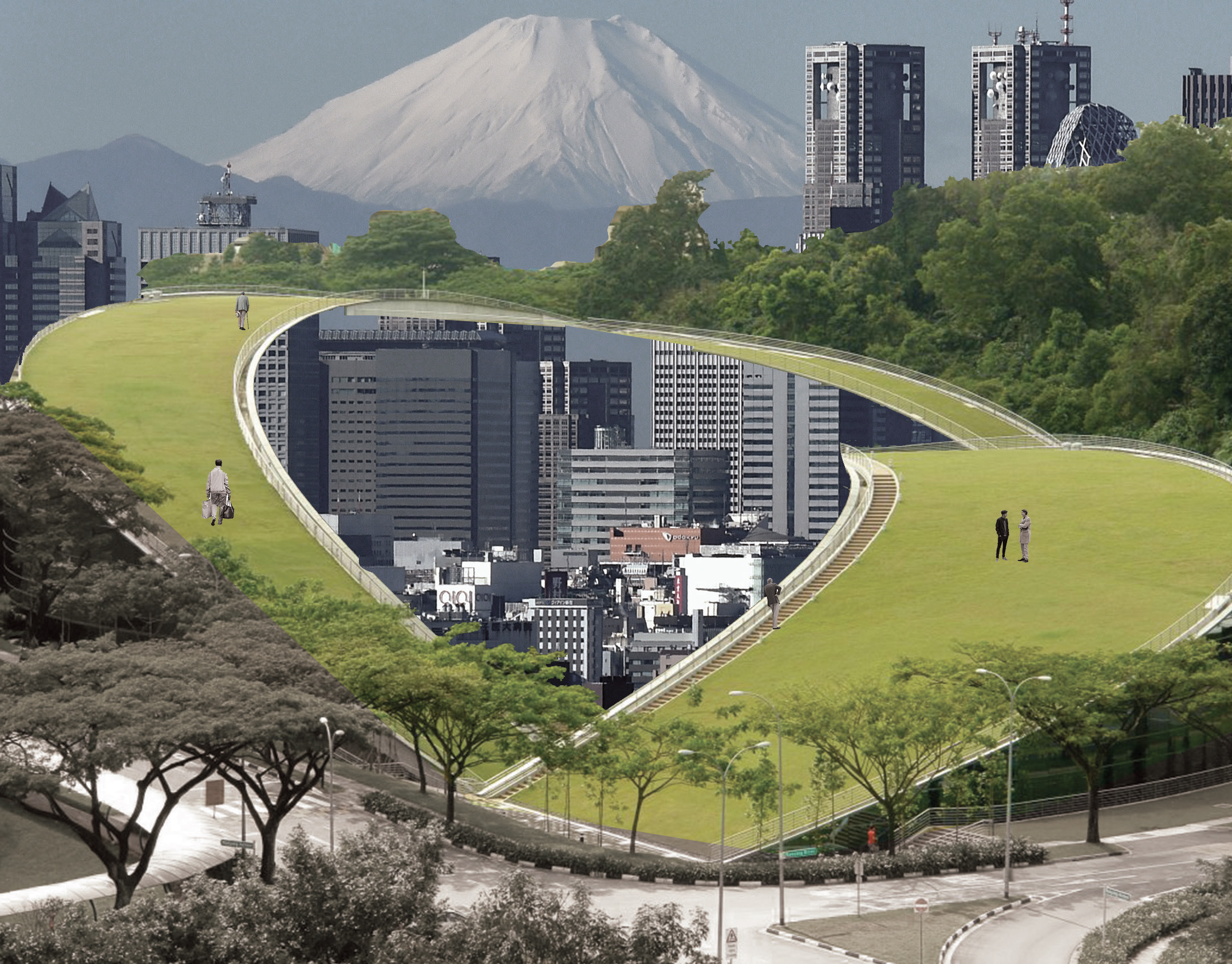

A Contemporary HofjeThis final design project has developed into a rich layering of our material research and considerations of Country. Beginning with hemp and cork, the proposal draws out their properties and opportunities for a new sustainable building ecology and weaves it into how we can best grow and cultivate it with respect to the local landscape. Building from this foundation, the proposal began to look towards historical typologies which had long provided enduring and adaptable homes to older women.

The studio was directed to the Dutch hofje, a 600-year-old urban block typology where homes or apartments are arranged around a private communal courtyard set within the city fabric. These intimate green oases provide specific disadvantaged demographics, such as the poor, elderly, disabled, or single parents, with a home in the middle of the city. These are spaces which tend to blend the lives of its inhabitants with the urban fabric, becoming an important form of social housing and community infrastructure. There are hofjes which remain today, their peaceful livability counterbalanced, and interacting with, the chaos and noise of the contemporary Dutch city. These surviving buildings in particular have endured thanks to their adaptability and flexibly, molding to the needs of its occupants as they age, as well as to the needs of our broader society.

It is this typology of the hofje which has the potential to meet current and future design challenges. Women over 45 are currently the fastest-growing population experiencing homelessness in Australia. Domestic violence, housing unaffordability, lack of employment opportunities, income, disability, carer needs or responsibilities mean that women often retire early, and with half the superannuation of their male counterparts. Researchers Samantha Donnelly and Sophie Dyring from Monash University stress the need for a best practice model to guide the housing of older women and ensure that our housing stock can accommodate the needs of this rising at risk demographic. Their research findings point to the importance of comfort, connection, independence, noise management, personalisation, privacy, and security. The design proposal sees a reimagining of the hofje in contemporary Sydney as an opportunity to provide these fundamental needs.

Older women have a range of different livelihoods, ambitions and needs. The proposal’s planning accommodates these by arranging semi-permanent prefabricated hemp wall panels around a set of permanent service cores and structure. Hemp’s durability yet, ability to biodegrade and then be regrown in less than 4 months encourages apartments and common spaces to be altered when necessary to suit the occupants needs. This ensures an enduring architecture which is highly adaptable through time. The proposal understands that wider occupancy needs change through time: apartments may grow to accommodate grandchildren, partners, family, friends, carers, or cater to accessibility requirements, allowing women to age in place. This is what creates a resiliant building. Common rooms on each level may also be altered to frame the most important to the most routine of life’s moments: Christmas lunches, birthdays, gardening, wakes, yoga, mahjong, bridge, workshops, art studios, coworking and reading. This is a design which recognises the required longevity and adaptability of each building component, from space to materials to structure. Specific materials are intelligently employed to serve each purpose. This is informed by Stewart Brand’s Six ‘S’s’ (Site, Structure, Services, Skin, Space Plan, Stuff), which orders building components based on their permanence. Site, structure and services, such as kitchens and bathrooms are seen to be permanent and require materials which are durable. The buildings skin, its finishes and spatial planning (dictated by the hemp panels and cork cladding) are expected to weather and be altered, therefore, they are made out of ‘hairy’ fibrous materials which can be regrown and decompose responsibly.

This design proposal is a composition of learnings from our material research, our respect for Country and a how older women live to create a contemporary hofje renewed as a new way of living in Sydney.

Room Types

When designing for older women it is important is to create spaces which become homes. This is a demographic which has a wide range of needs, needs which are rarely met in our current housing stock. As demonstrated in rising rates of homelessness and housing unaffordability, most homes and apartments are seldom equipped with the flexibility and accessibility required to accommodate the needs of older women. As a scarce typology with great demand these homes also come with a large price tag. Raising standards and awareness of these needs will help to diversify our housing stock making it more equitable and accessible.

Four apartment types and four common room types have been defined as floor plan configurations to provide flexibility. The apartment diagrams provide a rudimentary illustration of the potential occupant captured in each type, based on age, family dynamics and accessibility requirements.

Common Rooms bookend each side of the floorplan. They can also be altered to four types depending on what kind of apartments they service on each level to provide for amenity lacking on that floor. These might be another guest room, a working space, a lounge room or an indoor/outdoor patio for family gatherings.

Type A introduces the standard room type, designed to accommodate one occupant. Spaces and bathrooms are generous to provide wheelchair accessibility. All rooms are cross ventilated with access to the internal courtyard and street on opposite sides of the apartment.

Type B enlarges this standard room to create an apartment with a guest room for family or grandchildren. It results in an adjacent smaller studio room which can be allocated to a carer, guest, family member or less fortunate friend.

Type C joins two standard rooms to become a larger apartment. These are spaces which could be shared by two friends, a couple or those with larger budgets looking to downsize from their previous family home.

Type D separates the type C to create a separate studio room. This could be used by women requiring more space for mobility and a space for a semi-permanent carer or family member to reside.

Render Image - View out to communal courtyard from Apartment Type A

Apartment

Design

Older women spend more time in their homes than younger people, these home become vital to maintaining independence and wellbeing. These spaces should be customisable and organised around the daily needs of its occupant. Limited fixed furniture and an open plan allows women to tailor their spaces to suit their living requirements.

Kitchens must be universally accessible, easy to maintain, provide plenty of storage and be a welcoming environment encouraging residents to cook for themselves, ensuring that women can age in place. The floorplan stacks each kitchen and bathroom vertically on each floor creating an efficient service core which can be maintained even while the apartments spatial layout is altered. The kitchen and dining space is linked to the communal courtyard allowing women to enjoy warmer weather. Common rooms on each floor and the rooftop have communal kitchens providing the opportunity for residents to eat together.

Living areas receive light from the street and courtyard, as well as allowing for cross ventilation to help control heating and cooling costs. A large window with operable doors transforms the living area into an indoor balcony. A large hemp canvas awning controls light and shading to protect these spaces in the warmer months. A connection to the outdoors is important to maintain wellbeing. The proposal creates a internal living area which has flexible joinery and can suit each women’s different routines and activities. It may accommodate grandchildren sleeping over, a study or craft room. An outdoor verandah living space faces the internal courtyard, timber screens can be drawn across these windows to ensure internal privacy as required.

Bedrooms are highly valued as private, comfortable, and warm spaces. A generous sized room is important. It should permit great levels of personalisation to include curtains, storage shelves, freestanding furniture, and ample circulation. Direct natural light, awnings and cross ventilation ensures passive heating and cooling to lower energy consumption and ensure comfort. Large wardrobe storage spaces are required and must be easily accessible. These may accommodate a writing desk and space to store mobility vehicles but able to be concealed behind a sliding door to prevent a cluttered space.

Bathrooms are important parts of a woman’s daily ritual of washing, refreshing, and looking after oneself. Yet, they can be dangerous spaces and must provide ample universal circulation and space for a carer to assist, so women can age in place. Showers are provided with benches for sitting and detachable showerheads.

Kitchens must be universally accessible, easy to maintain, provide plenty of storage and be a welcoming environment encouraging residents to cook for themselves, ensuring that women can age in place. The floorplan stacks each kitchen and bathroom vertically on each floor creating an efficient service core which can be maintained even while the apartments spatial layout is altered. The kitchen and dining space is linked to the communal courtyard allowing women to enjoy warmer weather. Common rooms on each floor and the rooftop have communal kitchens providing the opportunity for residents to eat together.

Living areas receive light from the street and courtyard, as well as allowing for cross ventilation to help control heating and cooling costs. A large window with operable doors transforms the living area into an indoor balcony. A large hemp canvas awning controls light and shading to protect these spaces in the warmer months. A connection to the outdoors is important to maintain wellbeing. The proposal creates a internal living area which has flexible joinery and can suit each women’s different routines and activities. It may accommodate grandchildren sleeping over, a study or craft room. An outdoor verandah living space faces the internal courtyard, timber screens can be drawn across these windows to ensure internal privacy as required.

Bedrooms are highly valued as private, comfortable, and warm spaces. A generous sized room is important. It should permit great levels of personalisation to include curtains, storage shelves, freestanding furniture, and ample circulation. Direct natural light, awnings and cross ventilation ensures passive heating and cooling to lower energy consumption and ensure comfort. Large wardrobe storage spaces are required and must be easily accessible. These may accommodate a writing desk and space to store mobility vehicles but able to be concealed behind a sliding door to prevent a cluttered space.

Bathrooms are important parts of a woman’s daily ritual of washing, refreshing, and looking after oneself. Yet, they can be dangerous spaces and must provide ample universal circulation and space for a carer to assist, so women can age in place. Showers are provided with benches for sitting and detachable showerheads.

Ground

Floor Plan

The proposal sees the ground floor plan as an opportunity to interact with the street and to accommodate the daily routines of leaving and returning home. Main entries face Mitchell Road, one of Alexandria’s main thoroughfares. Residents enter the ‘hofje’ through a subtle portico where a security gate controls access. Letter boxes, lockers and seating allows women to organise themselves here as they leave and return. A garage to store bikes and mobility vehicles lies next to this entry. The remaining facade on ground level opens to the communal hall and public cafe. This stands as the main interface between the residents and the public. As a place where family, friends and the wider community can stop for a coffee, meal or relax. This hall and main entries open up to the internal courtyard. A few apartments, a fitness studio, bathrooms, cleaners store and workshop surround this courtyard and there is an additional entry through to Belmont Lane. Two service cores on either side of the development allow for vertical circulation to the floors above.

First

Floor Plan

The first floor plan permits the communal hall with a generous double height ceiling. With a verandah running around the courtyard this doubles as the main circulation route while also becoming the residents outdoor living space. For example, apartment Type A is predominantly shown on this floor. This smaller apartment type dictates the type of common rooms on each side. Here they are shown as an indoor/outdoor dining space for larger gatherings or family meals, and a lounge area as an additional break out space.

Second

Floor Plan

A mix of apartment types is shown on this floor. Including Type A, B and D. Common rooms show a lounge area and a space for a shared guest room.

Third

Floor Plan

A rooftop garden opens up the north elevation allowing as much winter sun as possible into the communal courtyard and rooms below. Apartments line the southern elevation with a communal rooftop kitchen garden shed.

Section

The section highlights a few of the more generous spaces in the proposal. This includes the double height communal hall on the ground level facing Mitchell Road and the relatively wide central courtyard. The northern facade sits one level below its southern counterpart, this is to allow more winter sun into the courtyard to improve access to light for the apartments along the southern elevation. The single loaded corridor arrangement of apartments allows them to be exposed to an external facade and the interior courtyard. This achieves natural cross ventilation used to cool the apartments in warmer months, and access direct sunlight during cooler parts of the year.

Elevation

The building’s main elevation on Mitchell Road presents a strong, monolithic, and stoic facade, reminiscent of the brutalist style of the late Modern movement, yet this allusion is playfully contradicted. Rather than using unyielding raw concrete to convey a sense of despotic permanence, corrugated panels made from hemp fibres and bio resin line the facade. This is a ‘hairy’ material which weathers and ages, transforming from a dark brown colour to a golden tint as it is exposed to UV light. As panels age and need to be replaced the facade will become a patchwork of panels which proudly display the passage of time though their patina. While the facade’s formal composition is simplistic, it does allow the focus to be on the materials. It becomes a billboard advertising the incredible potential of hemp, a visual to connection of a material which was locally grown. This contrast between the building’s rigorous orthogonal forms and decay can also be seen in the courtyard, where the warm cork panels line the facade expected to wear and tear and be replaced as time passes.

Facade &

Wall Details

Hempcrete panels are a return to monolithic architecture. This is opposed to the contemporary wall section which strives to be as thin as possible to include many different technologically complex layers to provide impeccable energy performance. While these buildings can reduce their energy in this way there is little regard to the embodied carbon of these materials, many of them based on carbon emitting, petrochemical and oil-based materials, and plastics. Hempcrete is an incredible material as it stores enormous amounts of carbon while providing remarkable thermal insulation.

These panels make up the external and internal walls of the building. They are supported by, and fixed to, a glulam timber post and beam structure with CLT floor slabs between each level.

Render Image - View into communal courtyard from main entry

Communal

Courtyard

Outdoor spaces, whether experienced directly or indirectly, are important for the health and wellbeing of older women, especially if some find it difficult to leave their homes to pursue it. A community of twenty-one women can be considered just intimate enough for this courtyard and the rooftop garden to become shared tranquil spaces. Spaces where women can spend time alone or interact with others. The proposal harnesses these spaces linking them to each apartment through the wraparound verandahs.

The courtyard is envisaged as a calm space, loose outdoor furniture can be moved to suit the needs of its users or follow the moving sun. A brick archway is retained from the previous building as a feature in the courtyard, acknowledging the sites previous industrial history as a factory and warehouse. This complements the use of brick paving, recycled from the demolition of this factory, throughout the ground floor. Life is focused around this courtyard increasing a sense of belonging for the housing community. Cork cladding is arranged in a brick pattern lining the verandahs. Cork is another ‘hairy’ material which is incredibly durable yet provides a warm tactility

The rooftop garden is a more energetic space. Raised informal garden beds are easily accessible for maintenance and can be co-opted to plant veggies, plants, and flowers. While its edges provide spaces to rest and engage with grandchildren or pets, friends and family or dry laundry. The workshop on the ground level and garden shed on the rooftop provide equipment storage for women who are active gardeners.

Render Image - View of the Communal Hall

Communal

Hall

The proposal’s communal hall is a celebration of our ‘hairy’ materials. Hempcrete panels line the double height space, hemp awnings shade the generous window openings, while the cork cladding is visble in the courtyard space beyond. This space is again flexible to become a cafe/restaurant or private hearth of the resident community, able to involve the public at a level suitable to the residents wishes. It becomes a public interface and buffer, lining the ground floor facade to sheild the noise and traffic from the rest of the building. Moveable loose furniture allows the space to become a large hall for special events and gatherings.

Render Image - Interior view of apartment living room

Passive

Design Strategy

Whilst this project forefronts a consideration of the energy used in the extraction and fabrication of our materials and buildings. Mining, harvesting, processing, transporting, and assembling all add to the amount of embodied energy and carbon emissions attributed to our building materials. Choosing materials which keep this embodied carbon low, and even negative has been one of the main goals of this project. Hemp and cork both hold incredible carbon sequestering potential, worthy of guiding impetrative action in our built environment through a new material culture in this era of climate crisis.

Whilst managing our material’s embodied energy is increasingly important, designing with passive design principles at the core of our practice is another necessity. Working with the local climate to introduce passive heating, cooling and ventilation creates an internal climate which is less likely to rely on energy consuming artificial conditioning units or central heating. Additionally. incorporating opportunities for the occupant to engage with and manipulate the temperature of their home with passive design is essential to keep energy costs low and living affordable.

Whilst managing our material’s embodied energy is increasingly important, designing with passive design principles at the core of our practice is another necessity. Working with the local climate to introduce passive heating, cooling and ventilation creates an internal climate which is less likely to rely on energy consuming artificial conditioning units or central heating. Additionally. incorporating opportunities for the occupant to engage with and manipulate the temperature of their home with passive design is essential to keep energy costs low and living affordable.

The buildings orientation allows all rooms to face north to receive low winter sun, warming the apartments in the cooler months. Apartments facing Mitchell Road easily achieve this, whilst the generous central courtyard allows sun into the rooms along the southern facade. This passive solar heating in winter is matched by introducing external hemp canvas blinds and eves to shade glazed openings to manage summer heat.

Passive heating in winter is complemented by the use of hempcrete panels. Their high thermal mass allows them trap heat gained during the day, and slowly release it as the room cools during the evenings and nights. This offsetting allows the apartments to maintain a stable temperature. Hempcrete panels are also fantastic insulators. Our 200mm thick walls achieve an R value of 4.0, well above the R2.8 required for Sydney’s climate zone. Insulation is critical to passive cooling helping to keep heat outside in summer, yet inside in winter.

Cross ventilation has been achieved in all apartments. Narrow single loaded corridors, operable windows and a open plan layouts allow for cooling breezes to pass through each apartment. This helps to draw out any heat gained in the apartments during the hottest part of the day, and replacing it with cooler external air, lowering the temperature. Ceiling fans provide reliable air movement to supplement breezes during still periods. Fans are especially useful in Sydney’s high humidity climate.

Axonometric Diagram - Passive Design

This diagram helps to illustrate the buildings main passive design strategies. A narrow floor plan wraps around a leafy central courtyard, openings positioned opposite each other on each side of the apartments permit breezes to pass through each space. This allows for passive cooling in warmer months. External operable vertical blinds shield these glazed openings from hot summer sun, preventing the interior from gaining heat. These same openings allow lower winter sun to penetrate into the apartments to warm the space in colder months. All walls are made from hempcrete panels which have a high thermal mass. This allows heat gained during the day to be stored and then released during the evenings. These same panels perform very well as insulators, keeping heat inside during cooler months, and outside during warmer months.

Axonometric Diagram - Belmont Lane Alternative

Belmont Lane

Alternative

During the design panel, the project was encouraged to explore an alternative facade treatment at the rear of the site facing Belmont Lane. This is a calm, leafy, residential laneway, home to many backyard gardens and garages. The diagram here presents a design iteration where the building is effectively flipped, moving the four-story mass from the southern facade along Belmont Lane to the northern facade along the much busier thoroughfare of Mitchell Road. This may be more appropriate as it lowers what could otherwise be considered quite an imposing facade along Belmont Lone to three stories. This height is then reduced to two stories by removing the top two central apartments to create a roof garden. This lower, staggered facade is less dominant and more considerate to the two-story volumes of the residential terrace houses it faces.

The proposal can still maintain its 21 apartments if the double height ceiling in communal hall and cafe facing Mitchell Road is reduced to a standard single floor height.

Whilst initial solar modelling deemed the original design compliant in allowing the appropriate level of winter sun to neighbours, the revision improves this solar access further.

However, this design change is not without its drawbacks. The now taller northern facade limits the amount of winter sun entering the courtyard and apartments along the southern facade.

The building’s design allows this height variation. Stacked service cores and an orthogonal structural grid allow apartments to be added and subtracted throughout the building’s lifespan. If the neighbourhood was to develop into a medium density zone in the future, and the local council had more of an appetite for taller buildings, floors could easily be added, and the service cores extended, to accommodate.

Material

Study

The proposal recognises that a building has many different moving parts. It questions how best to approach this complexity through an approch of sustainability, longevity, permanance and circular design. Stewart Brand breaks down a building into six layers in his book How Buildings Learn.

Site: This is the landscape and geographical setting of the building. It is recognised as perminant and innatly linked to Country. Buildings should be designed to leave minimal traces once removed.

Structure: Foundational and loadbearing elements are expensive to change so are relativley perminant.

Services: Plumbing, heating, ventilation, elevators, are a little more flexible yet should be considered stable elements of the building’s hardware.

Skin: Exterior surfaces are exposed to the elements and must keep up with technology. May be replaced for updates or repairs.

Space Plan: Interior layouts must be the most flexible part of the building, considered as its software. Able to be adjusted to accommodate changing occupants or programs.

Stuff: Chairs, desks, lamps, appliances, personal touches which change constantly

Site, Structure, Services, Skin, Space Plan and Stuff have been assigned specific materials which speak to their level of permanence.

The site is treated as a permanent grounding of the building. It is not expected to be altered drastically and therefore is given a low solid podium and paving using bricks taken from the demolished brick warehouse which previously occupied the site. As these bricks are an ancient material extracted from the earth, it was important recycle them and give them a longer life worthy of their carbon emitting and time intense process.

The building’s structure is treated as another permanent component. Foundational and loadbearing, these are elements which are expensive and complex to change throughout the building’s life. Whilst a rigid grid of glulam timber columns and beams has been set out in the floorplan, flexibility is introduced by creating room types which can adapt around this grid. Cross laminated timber (CLT) floor slabs compose the floors of each level. This rigorous and orthogonal grid is made from radiata pine timber which takes more than 35 years to grow. This time is valued by using these elements sparingly and giving them a high level of permeance.

Services have been grouped in vertical cores resulting in an efficient stacking of kitchens, bathrooms, and vertical circulation through each floor. Along with the buildings structure these cores are able to be retained whilst the space plan is altered around it to meet the building’s changing program. These are seen to be permanent and require materials, plumbing and wiring which are durable and so are expensive to alter continuously.

The buildings external skin can be afforded a less permanent material. Hempcrete fibre corrugated panels and cork cladding can be screw fixed to timber battens and are easily removable and replaceable if maintenance is needed on the facade. As a bio-composite material they are expected to weather and age with exposure to rain and UV. The hemp fibre panels can be regrown very quickly in less than 4 months and mature cork trees can be harvested every 9 years. Both these materials can be left to decompose back into the earth after their use.

The buildings space plan is dictated by prefabricated hempcrete panels. It is expected that apartments will change every 5-10 years as occupants age or change. This is facilitated by hemp which can be grown quickly and decompose after use. Demonstrating a very effective process of circular design.

Hemp

9 Points to Understand

Hemp is a ‘hairy’ material, as a fibre it is has the potential to be incredibly strong, yet able to weather and decompose when required. It’s use in architecture signals a repositioning away from the polished, inpervious and maintenance free materials which saturate our current material vocabulary. It’s construction is relatively low-tech compared to conventional systems. Skills involved are about care and control. Short training courses allow tradespeople to upskill quickly, but it is recommended to use a speciality subcontractor to supervise the process. Hempcrete blocks are made in specialist factories and assembled onsite just like conventional block walls. While hempcrete walls in-situ are slower and more labour intensive than conventional construction methods, off-site prefabrication of hempcrete panels is drastically more efficient. As these panels are custom made, economies of scale can reduce their cost if they’re intelligently designed to consist of only a few panel types.

Hemp shives and the lime binder are all widely available in Australia. Formwork is widely available as form ply or OSB. Structure is usually standard timber framing, widely used throughout Australian residential construction.

Hemp shives and the lime binder are all widely available in Australia. Formwork is widely available as form ply or OSB. Structure is usually standard timber framing, widely used throughout Australian residential construction.

Hemp has the ability to be grown locally creating a great connection between the farm and site. Minimising material travel distances is essential to keeping hemp’s embodied energy low. Hemp can be sourced from Australian farmers, NSW is the second highest producer in Australia. The secondary ingredient, lime, must be extracted from energy intensive mining, its is unable to be recycled once it is mixed with hemp and water, but can biodegrade into the soil.

Hemp cultivation absorbs carbon from the atmosphere and has the potential for a neutral or negative carbon footprint (if material transportation distances remain low) making it a very eco-friendly building material. Crop locations need to be carefully considered and avoid the destruction of native forests. Hemp could be used in crop rotation practices as it takes very little water to grow and greatly replenishes nutrients in the soil.

110kg of hemp hurd = - 202 kg (CO2 absorbed).

220 kg of lime binder = +94 kg (CO2 released)

Total sequestration = -108 kg

110kg of hemp hurd = - 202 kg (CO2 absorbed).

220 kg of lime binder = +94 kg (CO2 released)

Total sequestration = -108 kg